How Volatility Distorts Investors View of the Long Goal

We all know that we are supposed to buy low and sell high. Yet, most investors continue to demonstrate that they do the opposite: they buy high and sell low. Last year was no different. In 2018, Dalbar, an independent financial consultancy, found that the average equity fund investor lost twice the money of the broader index: -9.42% for the average investor versus -4.38% of the S&P500.[1]

This is the survey’s 25th year which has shown that year-over-year investor behaviour erodes their potential returns. I get it. Our evolutionary programming causes us to retreat at the first hint of threat. Think of TV shows like Planet Earth which feature a herd of grazing animals that speed off in panic at the sight of a predator. To boot, most of the grazers never saw the predator – they saw the heels of their friend running away. Our core tells us sell low when afraid.

Conversely, average investors tend to buy high. Buying high typically means buying when it feels good as humans prefer to fit within the group. Buying high isn’t necessarily a disastrous thing. If the underlying investment is strong and the investor’s time horizon is lengthy, they’ll be fine. Being at near the cycle high, however, increases the likelihood of a decline. But as long as the investor doesn’t sell low they’ll be fine.

I know I am speaking to the converted and experienced, but we are all human and perspective is helpful. (Also, I am not predicting a market collapse.)

Imagine a friend had the luck of receiving a large chunk of money in 2007 and invested it on the eve of the financial crisis: October 2007. Then, the S&P500 was 1,549. Today, over a decade later it is almost 3,000 – double. The mood and sentiment in October 2007 was positive – times were good – it felt easy to invest. But then weeks later, the markets endured an arduous 50% decline to 735. Even looking back knowing where we are today, we can sympathize with your friend. They didn’t get to enjoy any positivity around their investments for over 5 years. Hopefully, they would have had the courage and perspective to reflect on their plan and time horizon. And be patient.

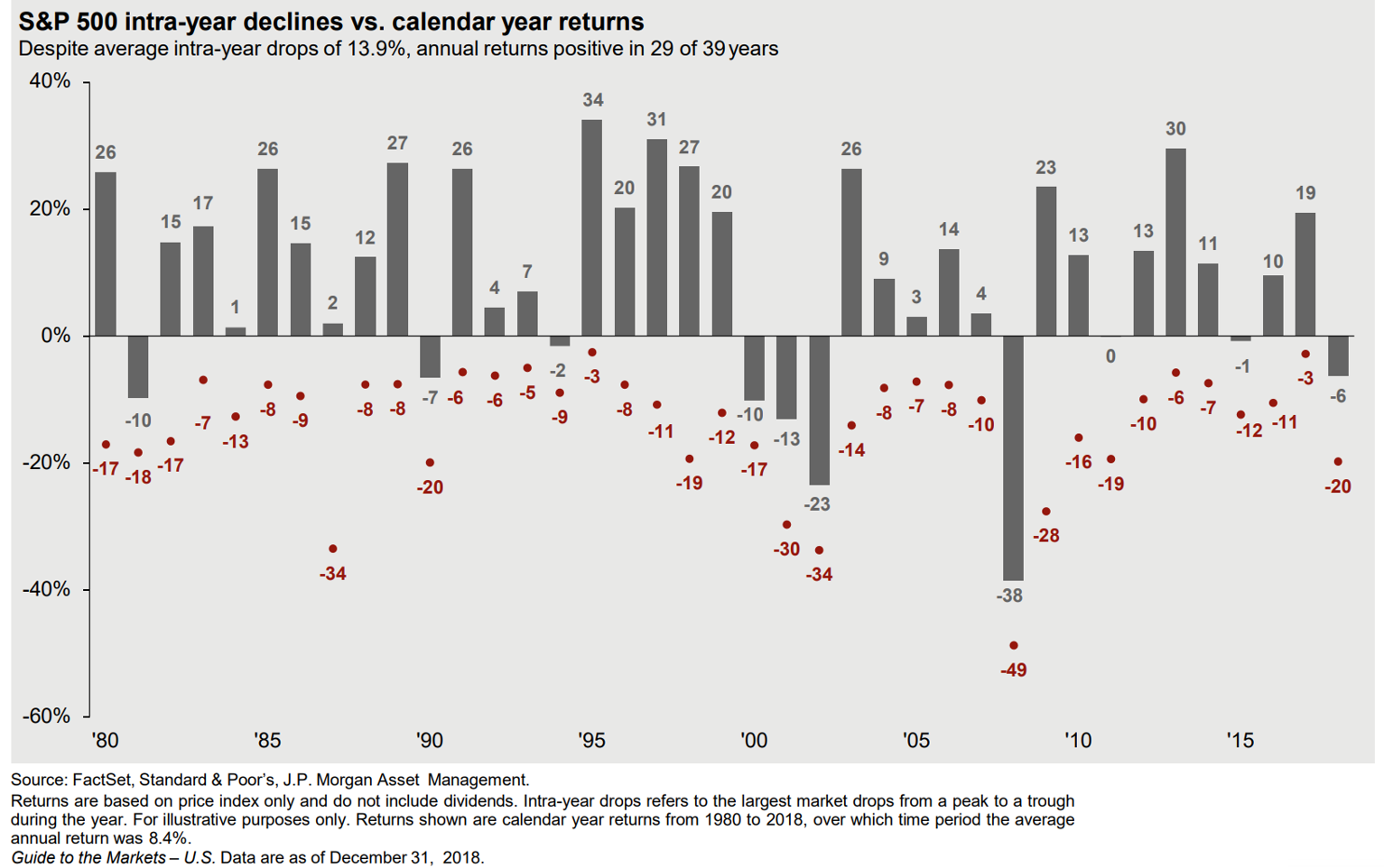

The financial crisis was a rare black swan event. More routinely it is the perpetual market declines that strain our resolve (the financial press and internet don’t help) rather than the evidence of long-term performance holding us up. We see predators. We see others running away. The chart below shows the calendar year returns of the S&P500 (grey bars) versus the largest decline of the year (red dot). In 2012, for example, at one point the market had dropped by 10% but finished up 13% on the year. Think about 1987’s Black Monday. We muse about its rapid plunge of 34% yet few discuss how it finished the year up 2%. The drops are temporary while the trend is upward.

https://maminvesting.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Annual-Returns-Intra-Year-Declines-12-31-18.pdf

https://maminvesting.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Annual-Returns-Intra-Year-Declines-12-31-18.pdf

In business school, we would analyze case studies of businesses and develop a series of options for the ‘hypothetical’ management team. The last option would invariably be “Do Nothing” or “Stay the Course.” At the time I always thought this addition was a copout and lacked creativity.

Now, I know that in financial planning the option of sticking to the plan is not a copout and is typically the best, and toughest, course of action.

Let me know if you have any questions or anything to add.

[1] https://www.dalbar.com/Portals/dalbar/Cache/News/PressReleases/QAIBPressRelease_2019.pdf

Quick Links

Privacy | Disclaimer | © 2019 Assante Wealth Management

Know your Advisor: IIROC Advisor Report

Assante Capital Management Ltd. is a Member of the Canadian Investor Protection Fund and Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada. The services described may not be applicable or available with respect to all clients. Services and products may be provided by an Assante advisor or through affiliated or non-affiliated third parties. Some services and products may not be available through all Assante advisors. Services may change without notice. Insurance products and services are provided through Assante Estate and Insurance Services Inc.